Egyptian Marriage Practices (Part 2)

Khalid Mikawy

The engagement:

If the couple agreed, they would announce their engagement, which is a period that allows them to get to know each other better.(1) During this time, the couple would wear wedding rings (Debla) on their right-hand ring finger. The bride’s ring would be made of gold, while the groom’s ring would be made of silver. They can choose to engrave their names on the rings as well.

In some communities, it is not allowed for the groom to see his bride during the engagement period. For example, in Siwa, the groom may ask to marry the bride at a young age, around 10 or 12 years old, to secure her as his future wife and prevent other suitors from pursuing her. However, he must wait several years, typically around 6 years, until she reaches an appropriate age. Once he has asked for her hand, he cannot change his mind. During this period, the groom would visit the bride’s family and stay in the “Marbo’a,” the Bedouin salon. The bride would serve him tea, and then she would leave while the groom stayed behind to talk with her brother.(2) Similarly, in Nuba, the groom is prohibited from seeing the bride alone, even if they happen to cross paths on the street. It is believed that by maintaining this distance, the groom’s desire for the bride will remain strong, leading to a more memorable wedding night.(3) In certain families in Munufya, Delta, the groom is also restricted from meeting the bride alone until three days before the wedding ceremony or Henna night.(4) The typical duration of an engagement is usually one year or less, but it can sometimes extend to three years or more.

In Christian families, an engagement contract called “Je Peniot” is signed by the parents of the couple in a public ceremony officiated by a clergyman. This contract can be dissolved at any time because engagement is merely a public declaration of the intention to marry and does not grant either party physical rights over the other.(5)

Among Muslim communities, engagements can be organized in one single event or divided into two separate events. In the case of a two-event engagement, the first event is called “Qira’at Al-Fattha,” which involves the recitation of the first chapter of the Qur’an. This private meeting brings together the two families of the couple to discuss and finalize all the details of the engagement. Once both families reach an agreement, they recite the first chapter, “Fattha,” as a confirmation of their agreement. Subsequently, the bride’s family determines the date for the engagement party, which can be considered the same event as the Fattha, but with the attendance of additional guests.

In Kalabsha, Nuba, during the Fattha ceremony, the groom visits the bride’s family home to meet her father, recite the Fattha, and discuss the details of the engagement, including setting a date. Similarly, in Salamon village, Munufya, Delta, they recite the Fattha and agree on the value of the Shabka (bride price), costs of furniture, and the responsibilities of each party. The groom, accompanied by his family, often brings gifts such as boxes of cola, fruits, and sometimes a wedding ring as well.(6)

The engagement party is typically organized by the bride’s family and can take place in various venues, such as the bride’s family home, a hotel, or a fancy restaurant. This event gathers the groom’s family, along with close friends and relatives of the couple. It serves as a precursor to the wedding day and can be an extravagant affair with elaborate decorations, various forms of entertainment, and a lavish feast. During the engagement party, the groom presents the Shabka and the wedding ring, which is worn on the right hand.(7)

In Kalabsha, Aswan, the groom, accompanied by his friends and relatives, visits the bride’s house and brings the Shabka. As part of the celebration, two sheep are slaughtered, and the female members of the bride’s family prepare a meal for the guests. Singing and dancing ensue during the festivities. (8)

In Nuba, the engagement day is called “Rebat.” The groom pays a sum of money as part of the engagement ritual. The bride’s family offers dates (Fanty) and popcorn to the groom’s father, and tea is served to the guests. After enjoying the tea, the guests depart. The groom and his male relatives are not allowed to see the bride directly, so he relies on his female relatives to describe her to him. Alternatively, he may wait for her in the street while she goes to the Nile with her friends to fetch water. (9)

During the engagement party, the groom presents the Shabka, which can vary in form. In Kalabsha, Aswan, there is no specific Shabka, and instead, the groom buys clothes, perfumes, and other necessities for the bride. However, nowadays, it has become common for the groom to pay a golden Shabka. In Damietta, Delta, the value of the Shabka is determined by the bride price. For example, if the bride price is 15,000 pounds, the bride’s father would pay an additional 15,000 pounds to purchase a golden Shabka. In El-Ghar village, Sharqya, the groom presents a variety of items along with the golden gift, such as clothes, lingerie, and the dress the bride will wear during the wedding party. These objects are displayed and hung on baskets during a parade that proceeds towards the bride’s house. Additionally, boxes of fruits, including Gawafa, grapes, and oranges, along with six large towels, cola boxes, and soaps are also included. The parade is accompanied by singing. After a week or ten days, the bride reciprocates by sending a meal consisting of onions, macaroni, noodles, and rice. A group of women carries these items in another parade, singing and ululating as they head to the groom’s house. On the night of the Shabka, the bride’s family sends dinner to the groom’s family, and on the wedding night, they send dinner to the couple’s new home as well. The groom bears the costs of the Shabka night (“Kosha”) and the DJ. (10)

Some grooms pay the bride price during the engagement party, while others pay it during the signing of the marriage contract (Katb El-Ketab) for Muslims or the wedding ceremony for Christians.

During the signing of the contract:

Marriage contracts were not officially documented until the Ptolemaic era.(11) The contract would include certain vows made by the groom, such as considering the woman as his wife, paying the bride price, acknowledging that the furniture belongs to her and should be returned or compensated for if their eldest son inherits all their wealth, and specifying the amount of money to be paid in case of divorce.(12) The contract would be written down in the bride’s family house.(13)

Having a marriage contract allows women to have ownership rights, especially in the event of divorce or the death of their husbands.(14) It also provides official recognition of the marriage. Among the Bedouins of Sinai, in earlier times, there were no contracts or documentation. Instead, the groom would visit the bride’s father and ask for her hand in marriage. The bride’s father would then give the groom a green branch called “El-Qosla” as a symbol of acceptance and blessing.(15)

In Orthodox Christian wedding ceremonies, which usually take place in a church, the ceremony lasts approximately 45 minutes and includes hymns, prayers, Bible readings, the exchange of rings, anointing with Holy Oil, the blessing of the crowns, and a priest’s admonition. (16)

Most Muslims sign the marriage contract, known as “Katb El-Ketab,” a few days to a month before the wedding party. However, in some cases, such as in Nuba and among Bedouins, the contract is signed on the same day as the wedding party. This contract holds official status for Muslims and includes the details of the “Mahr” (dowry) and “Mo`akhar” (additional payment) that the bride receives in the event of divorce.(17) These terms are written down in the contract.

During the “Katb El-Ketab” ceremony, the couple exchanges oaths and signs the marriage contract. A cleric officiates the ceremony and registers the contract with the appropriate government authorities. The bride’s father, uncle, or brother, along with the groom, join hands and read the contract and the first chapter of the Qur’an, known as “Fattha.” (18)

In Nuba, a week before signing the contract, a woman carries a plate containing “Ogel,” which is the wooden jar that will hold the perfumes for the wedding ceremony. She wanders around the village singing songs praising the families of the groom and the bride. This serves as an invitation for all women to participate in helping the bride’s family with the preparations for the wedding ceremony. Women then gather at the bride’s house and assist with tasks such as grinding maze, baking bread, and preparing dates and popcorn, all while singing. (19)

In Damietta, Delta, the contract is signed at mosques. In the past, it was common to sign the contract at the couple’s new home on the wedding night. However, nowadays, the contract signing may occur a month or 20 days before the wedding night. In Zagazig, they consider the end of the Hijri month as an auspicious time to sign the contract. Typically, it is signed after sunset, around 3 to 4 days before the wedding party. (20)

In Nuba, during the contract signing, the groom gathers with his friends, a Ma`zoon (cleric), the mayor, some community leaders, and the bride’s relatives. The Ma`zoon begins by reciting the Fattha and offering prayers for the couple. Then, he proceeds to write down the contract. The bride does not attend the signing; instead, her father represents her. After the contract is signed, the bride presents the bride price, along with some clothes and the Shabka. Following this, the guests partake in a dinner, with the bride’s family covering the expenses for the night. Subsequently, the groom enters the bride’s room accompanied by his mother, some female relatives, and the bride’s family. He unveils her face, and then they return to their friends who celebrate them with songs. Finally, everyone sits down for dinner. After dinner, the groom’s friends request him to “Gawishna,” which involves smashing perfumes in a basalt plate. They do this for a while, and then the young girls continue singing. (21)

In Bashari, the groom arrives in a camel parade and designates a spot where his friends and relatives start setting up the tent, which will serve as his future house. He presents gifts such as Henna, clothes, shoes, and jewelry, and gives a gift to the bride’s mother. At noon, a camel is slaughtered, and the women begin cooking. The groom’s friends assist him in changing into his new clothes and then he sits, holding his sword, and greets his guests. At night, male guests and elders gather to sign the contract, which entails reciting the Fattha without signing any official documents. Following this, they proceed to visit the bride’s family, who are not permitted to attend the contract signing. (22)

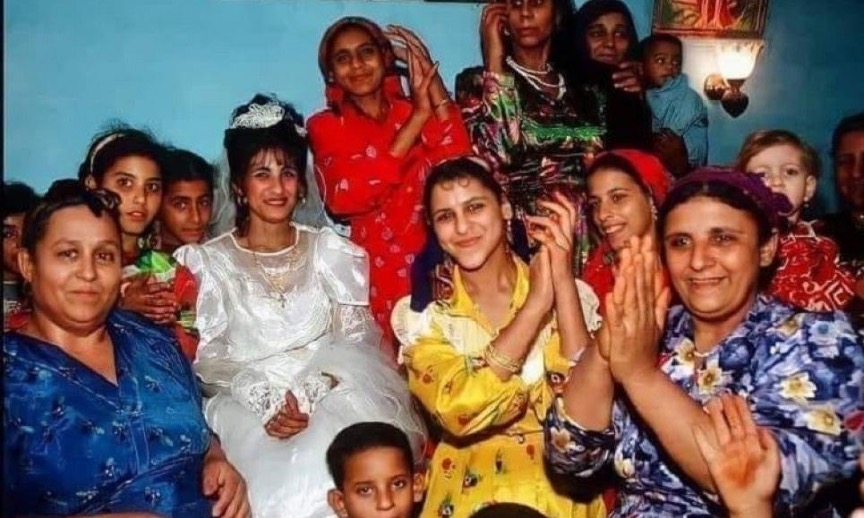

Henna night:

A day or two before the wedding ceremony, Egyptian women gather for a “Henna party” dedicated to the bride, along with her female cousins and friends. (23) This themed celebration involves hours of singing, dancing, and adorning the bride’s hands and feet with henna tattoos. The tradition of henna dates back 5000 years and is believed to bring happiness and good fortune. While this party is typically private and exclusive to women, sometimes it may be followed or accompanied by a separate public celebration held in the streets by men. (24) It is less common for the groom to have his own henna party with his male cousins and friends.

In Nuba, separate parties are organized for both the groom and the bride, where friends are invited to sing and dance. During these celebrations, the bride and groom are adorned with henna by their respective grandmothers or aunts. The groom also receives Nuqta, a form of celebration or tribute, from his friends. Following the henna application, all the guests gather for dinner together. The next morning, there is a procession in which the groom, accompanied by his friends, relatives, and religious teachers (“Sheikhs”), walks around the village in a parade. (25)

References:

1- COMPLETE LIST OF EGYPTIAN WEDDING TRADITIONS, available on: https://www.clarencehouse.com.au/wedding-tips/complete-list-of-egyptian-wedding-traditions/4

2- Folklore Magazine, issue 85, Jan.- Feb.- March 2010, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Egyptian Folk Wedding Celebrations”, p. 62-64.

3- Folklore Magazine, issue 100, Jan.- Dec. 2015, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Nuba`s Wedding Ceremonies”, by Safwat Kamal, p. 53.

4- Folklore Magazine, issue 85, Jan.- Feb.- March 2010, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Egyptian Folk Wedding Celebrations”, p. 65.

5- EGYPTIAN WEDDING GUIDE, available on: https://julianribinikweddings.com/egyptian-wedding/#:~:text=When%20the%20couple%20gets%20engaged,a%20marriage%20that%20never%20ends

6- Folklore Magazine, issue 85, Jan.- Feb.- March 2010, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Egyptian Folk Wedding Celebrations”, p. 64-65.

7- EGYPTIAN WEDDING GUIDE, available on: https://julianribinikweddings.com/egyptian-wedding/#:~:text=When%20the%20couple%20gets%20engaged,a%20marriage%20that%20never%20ends

8- Folklore Magazine, issue 85, Jan.- Feb.- March 2010, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Egyptian Folk Wedding Celebrations”, p. 64-65.

9- Folklore Magazine, issue 100, Jan.- Dec. 2015, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Nuba`s Wedding Ceremonies”, by Safwat Kamal, p. 53.

10- Folklore Magazine, issue 85, Jan.- Feb.- March 2010, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Egyptian Folk Wedding Celebrations”, p. 65-66.

11- Ancient Egypt: from Ptolemy II to Ptolemy IV, By: Selim Hassan, Vol. 15, p. 645-667

12- Ancient Egypt: From Ptolemy V to Ptolemy VII with a chapter about worshipping animals in late eras, vol. 16, by Selim Hassan, p. 582- 595

13- Ancient Egypt: from Ptolemy II to Ptolemy IV, By: Seliem Hassan, Vol. 15, p. 645-667

14- Ancient Egyptian Wedding Customs, available on: https://www.historyforkids.net/ancient-egyptian-wedding-customs.html#:~:text=In%20ancient%20Egypt%2C%20there%20wasn,families%20would%20also%20exchange%20gifts.

15- Folklore Magazine, Issue 5, Feb. 1968, Ministry of Culture, The General Egyptian Publishing Organization, “Sinai: its customs and traditions”, by Mohammad Tolba Rizq, p. 91-92.

16- EGYPTIAN WEDDING GUIDE, available on: https://julianribinikweddings.com/egyptian-wedding/#:~:text=When%20the%20couple%20gets%20engaged,a%20marriage%20that%20never%20ends

17- COMPLETE LIST OF EGYPTIAN WEDDING TRADITIONS, available on: https://www.clarencehouse.com.au/wedding-tips/complete-list-of-egyptian-wedding-traditions/

18- Egyptian Wedding Traditions Worth Learning About, available on https://www.weddingdetails.com/egyptian-wedding-traditions-worth-learning-about/#:~:text=Traditional%20Egyptian%20wedding%20gifts%20include,are%20a%20symbol%20of%20fertility

19- Folklore Magazine, issue 100, Jan.- Dec. 2015, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Nuba`s Wedding Ceremonies”, by Safwat Kamal, p. 57.

20- Folklore Magazine, issue 85, Jan.- Feb.- March 2010, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Egyptian Folk Wedding Celebrations”, p. 66-67.

21- Folklore Magazine, issue 100, Jan.- Dec. 2015, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Nuba`s Wedding Ceremonies”, by Safwat Kamal, p. 63-69.

22- Folklore Magazine, Issues 30-31: Jan.- June 1990, The General Egyptian Book Organization publications, “Bishari: the desert`s dwellers”, by Nadia Badawy, p.93-94

23- COMPLETE LIST OF EGYPTIAN WEDDING TRADITIONS, available on: https://www.clarencehouse.com.au/wedding-tips/complete-list-of-egyptian-wedding-traditions/

24- EGYPTIAN WEDDING GUIDE, available on: https://julianribinikweddings.com/egyptian-wedding/#:~:text=When%20the%20couple%20gets%20engaged,a%20marriage%20that%20never%20ends

25- Folklore Magazine, issue 100, Jan.- Dec. 2015, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Nuba`s Wedding Ceremonies”, by Safwat Kamal, p. 58- 63.