Egyptian Marriage Practices (Part 3)

Khalid Mikawy

Wedding party/ceremony:

In ancient Egypt, couples who wished to get married would simply move in together without a formal wedding ceremony as we have today.(1) However, over time, the wedding ceremony became an integral part of the marriage process.

The wedding ceremony typically begins with the “Zaffa” procession. Once the groom receives his bride from the hairdresser or coiffeur, decorated cars adorned with ribbons and flowers, driven by friends and relatives, accompany them in a lively procession with blaring horns.(2) In rural or Bedouin areas, the groom may arrive on a camel as part of the procession. In some regions, relatives may celebrate the procession by firing gunshots into the air, a tradition that has been replaced by fireworks in urban areas.

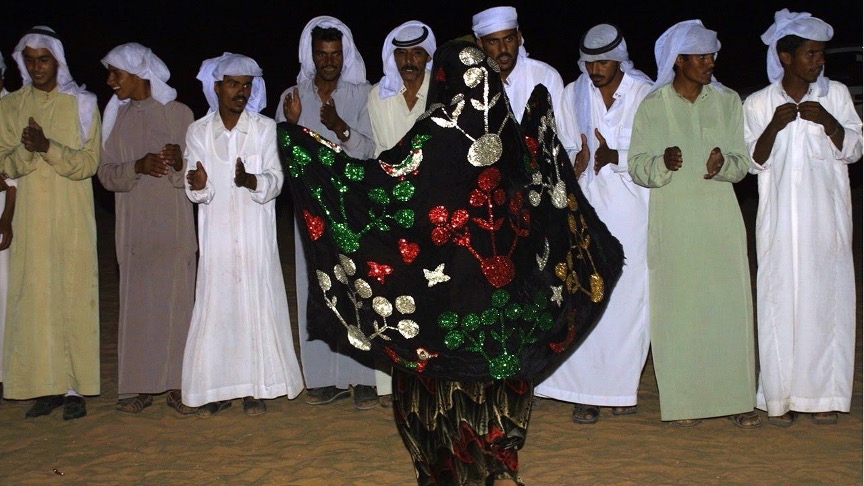

The second part of the Zaffa begins when the groom and bride enter the hall or venue, accompanied by a band playing drums and trumpets that welcomes them loudly. Friends and some of the guests join in the celebration by dancing and clapping, while women express their joy by giving “Zaghrouta” or ululation.(3) Zaffa bands sing traditional songs that praise the couple and celebrate their union. Depending on the budget and agreement with the couple, the band may also perform traditional folklore shows such as “Pharaonic Zaffa,” “Damittan Zaffa,” “Alexandrian Zaffa,” or “Baladi Zaffa.”

After the Zaffa, the bride and groom proceed to sit on the “Kosha,” which is a raised seating area adorned with an elegant sofa and beautiful regal-looking decorations. This allows them to receive and greet their guests, as well as take memorable photographs.(4)

After some time of dancing, including slow dances between the couple and group dances with friends and family members, the couple is invited to return to the Kosha or proceed to the Cake Cutting ceremony. During this ceremony, they can cut a multi-layered cake and lovingly feed each other a slice. They also have the opportunity to enjoy a refreshing drink called “Sharbat,” which is a sweet beverage made with fruit and herbs.(5) Additionally, they symbolically switch their wedding rings from their right hands to their left hands, marking the transition from the engagement phase to married life.(6) The wedding ring itself is believed to have originated from Ancient Egyptian culture and represents the unending circle of eternal matrimony.(7)

Cutting the cake signifies the beginning of the wedding feast, which is an integral part of all Egyptian wedding ceremonies. It is during this feast that a delicious meal is served to the guests. After enjoying the meal, the celebration gradually comes to an end. Some guests may take their leave, while the closest friends and family members remain to accompany the couple to their new home. The couple is showered with grains, as a symbol of fertility and lifelong prosperity,(8) and salt, to protect them from the evil eye.

In the Bishari tribe, the wedding party lasts for seven days. Each day, from the first to the 40th, the bridesmaids, known as “Wazirat,” lead the bride to the groom’s tent at sunset. They then return to take her back to her family’s house at sunrise. This tradition stems from the Bishari belief in the sun and their customs, which prohibit the couple from meeting while the sun is in the sky.(9)

Sabahya:

“El-Sabahya” marks the first day of marriage, as the couple is finally united. From the first day of their marriage, they receive visits from their families, relatives, and close friends, which can extend for a month or more. These visits serve to congratulate them, present gifts, and ensure that they have successfully consummated their marriage.

2- The bride price: How is it determined?

In Ancient Egypt, there is no evidence of a bride price, or at least no documents have been found to prove its existence. However, over time, terms such as “Mahr,” “Shabka,” “El-Qaima,” and “Mo’akhar” emerged and became essential components of the marriage contract. Let’s clarify their functions and values.

Function:

There are two main types of bride price: “Mahr” and “Shabka,” which are paid before the marriage, and sub-bride prices: “El-Qaima” and “Mo’akhar.” “Mahr” is a dowry or bride price that the groom pays to the bride’s family to contribute to the purchase of furniture for their future home.(10) Essentially, “Mahr” is a gift to the bride, giving her the freedom to use the money as she wishes.(11) However, in reality, “Shabka” emerged as a separate gift of gold and precious gems that the groom presents to his bride.(12) Consequently, “Mahr” is now entirely paid to the bride’s family, while the “Shabka” is paid directly to the bride.

The function of the bride price is to safeguard the bride’s rights and provide her with personal property separate from her husband’s financial obligations, such as her daily, monthly, and yearly allowance, inheritance rights, or the ability to share in her husband’s wealth with their future children.

To secure these rights, marriage contracts are established. The oldest contracts date back to the Ptolemaic era and include, in addition to the bride price, “El-Qaima,” which covers all the items and appliances the bride purchases for her new home,(13) and “El-Mo’akhar,” which is the post-marriage price to be paid to the wife in case of divorce.

This can be seen, for example, in marriage contracts dating back to August 24th, 264 B.C. (the 21st year of Ptolemy II)(14), another one from the era of Ptolemy III,(15) and a third one from the 17th year of Ptolemy III.(16)

However, in certain tribal communities in Egypt, such as the Nuba and Bedouins, the bride price serves primarily as compensation to the bride’s family for the loss of their daughter, who contributes economically to household work or as a social member transitioning to another family. It also acts as a guarantee for the bride that if she is mistreated or humiliated by the groom’s family, she will receive compensation. This interpretation sheds light on the common resistance rituals observed in marriage ceremonies in Nuba.(17)

Value:

Generally, some families in both urban and tribal communities still associate the value and status of the bride with the high or expensive nature of the bride price gift. However, the bride price varies based on time, community, and financial capacity. For example, in the 1960s in Nuba, the bride price ranged from 5 to 10 L.E. (Egyptian pounds), while the post-marriage price was 10 to 15 L.E. Additionally, jewelry gifts such as “Qosat El-Nour/Rahman” (a golden triangle worn on the bride’s forehead to signify her married status), “Gakad” (a six-line golden necklace with a golden “Mashaa Allah” (God Praise) pendant in the middle), “Shesh” (a silver bracelet), as well as a set of clothes and perfumes were included.(18)

In Sinai during the 1960s, the bride price ranged from 1 to 5 camels for cousins and could reach up to 20 camels if the bride was not a cousin.(19) In the Bishari tribes, the bride price consists of a couple of camels, along with some sheep and goats, and is shared among the fathers of the bride and groom. The bride’s uncle (her mother’s brother) also has a share in the form of a camel or its equivalent value, in addition to other gifts that the groom purchases for the bride and her family.(20)

- The financial costs of the traditional marriage ceremony

Generally, it is the groom who bears the responsibility for the costs of the marriage ceremony. However, due to various financial challenges, traditions have evolved in dealing with this issue.

In Munufya, Delta, during the engagement negotiations that follow the recitation of the first chapter of the Qur’an, known as “Qira’at El-Fatha,” the two families agree on the expenses related to the furniture of the future house. The groom takes responsibility for the furniture, while the bride is responsible for carpets and curtains.(21)

In the Bishari tribes, the groom is expected to cover the costs of all the marriage ceremony events, which typically span a duration of 7 days. Additionally, during these 7 days, the groom is required to sacrifice a camel, specifically on the first and seventh days.(22)

However, in general, the financial burden is shared between the two families, particularly concerning the furniture for the new house. In urban areas, it is customary for the groom to cover the expenses of the marriage ceremony, including booking the venue or hall and arranging the honeymoon vacation. However, in some cases, the bride’s family may also contribute to alleviate financial obstacles and share the costs with the groom.

- The wedding attire

In Ancient Egypt, the bride would wear a long dress made of linen, accompanied by a net that covered her head. If she possessed any jewelry, she would wear it to showcase to her husband (23). The groom would usually don a ceremonial tribal outfit or a custom robe (24).

In modern Egypt, couples have the option of embracing traditional attire or incorporating modern elements. Brides may opt for a white wedding dress or a jewel-toned gown, often accompanied by a veil as a symbol of modesty. Grooms can choose to wear a black suit, tuxedo, or ceremonial ethnic attire. Some couples even have multiple ceremonies to honor traditional customs or change outfits throughout their special day (25).

The choice of attire for the couple is influenced by the wedding location. Urban ceremonies tend to be more modern, with the bride wearing a typical white dress and the groom donning a tuxedo or suit for Christian weddings. On the other hand, weddings outside the city tend to be more conservative. Brides wear modest dresses that cover their bodies, often accompanied by a veil, while grooms wear custom robes for the ceremony (26).

As for the guests, there are generally no strict limitations on attire. Dressy or semi-formal clothing is considered acceptable. Opting for a nice, colorful dress or suit is recommended. However, it’s important to note that shorts are considered undergarments in Egypt and are not allowed to be worn (27).

- Gifts:

Gifts in Egyptian weddings hold significance for various parties involved, including the groom, bride, family members, and guests. These gifts serve to celebrate the newlywed couple and assist them in establishing their new household, fostering happiness in their new life together. While some gifts are considered debts to be repaid in case of divorce or separation, others are exchanged between the groom and the bride during the engagement period and leading up to the marriage. These mutual gifts can range from teddy bears, hearts, and medals to chocolate boxes, money, and clothes. The gifts by friends, relatives or guests are considered as a debts to be repaid in similar events.

When it comes to gifts from guests, typically friends and family members, they may offer money, knick-knacks, house decor such as vases or china, or even chocolates (28). In specific regions like Nuba, the groom’s father may provide essential items like sugar, tea, flour, and margarine, which can support the couple’s household for at least a month. In some Nubian tribes, the bride stays at her family’s home for a designated period, and the groom’s mother presents her with new clothes as a gift when she emerges for the first time. In other Nubian traditions, the couple may be hosted by the bride’s family for an extended period, ranging from 40 days to one year or even three years, during which the groom takes on no financial responsibilities, and the bride’s mother manages the household chores (29). In Sinai, relatives and neighbors often offer gifts in the form of camels, sheep, goats, or money (30).

The traditional marriage ceremony holds great significance within the community and for the families of the bride and groom. Nubians, for instance, view marriage as a confirmation of their bond and a reason to partake in a grand celebration that involves everyone (31). Similarly, in Bishari culture, marriage is a matter of common interest,(32) and the ability to give birth defines a woman’s role within the tribe, emphasizing the importance of family and lineage (33).

Note: Please keep in mind that cultural practices and traditions can vary within different regions and communities in Egypt.

- The significance of the marriage ceremony in terms of social status, family honor, and community recognition:

The marriage ceremony in Egypt holds significant importance in terms of social status, family honor, and community recognition. It is seen as a reflection of a family’s status and reputation within their social circle. A grand and well-organized wedding is often considered a symbol of high social standing and prosperity. Families strive to arrange elaborate ceremonies to showcase their wealth, hospitality, and ability to provide for their children.

The success and grandeur of the wedding ceremony contribute to the family’s honor and prestige. Hosting a memorable event reflects positively on the family’s reputation and can enhance their standing within the community. Conversely, a poorly organized or modest wedding may be viewed as a sign of lower social status.

Community recognition plays a significant role as well. Egyptian society places great importance on communal participation and celebration. A well-attended and lively wedding ceremony signifies community support and endorsement of the union. It fosters a sense of belonging and strengthens social bonds within the community. The community’s involvement and presence at the wedding also extend support and blessings to the newlywed couple, symbolizing their acceptance and integration into the wider social fabric.

In summary, the marriage ceremony in Egypt carries substantial implications for social status, family honor, and community recognition. It serves as a platform for families to display their standing, while the community’s participation reinforces the importance of communal bonds and support in celebrating the union of two individuals.

Ancient Egyptians believed that “if you are a good man, you should establish a household and marry a virtuous woman who can bear you sons.” They held the belief that a man’s happiness and respect in society were closely tied to having many sons.(34) This sentiment is reflected in ancient instruction literature from the Old Kingdom, which advised individuals to marry at a young age and start a family.(35)

The ancient Egyptians placed great importance on the institution of marriage and the procreation of children. They saw it as a fundamental aspect of a fulfilling life and a means of perpetuating their lineage. Getting married and having children at a young age was encouraged, as it was believed to bring happiness, fulfillment, and social respect.

It is worth noting that these beliefs were reflective of the societal norms and values of ancient Egypt, and they may not necessarily align with contemporary perspectives.

If you examine statues of ancient Egyptian couples, you will notice that the man and woman are depicted standing side by side, with the woman placing her arm around the man’s waist, symbolizing their partnership. This idea of mutual support and collaboration influenced the Egyptian sculptor “Mahmoud Mokhtar” in the early 20th century when he was commissioned to create a statue representing the Egyptian renaissance and rebirth. He sculpted a female farmer standing beside a sphinx, symbolically supporting it by placing her arm around its neck.

In ancient Egypt, wealth and resources were shared between spouses in a specific manner. The man was typically allocated two-thirds of the wealth, while the woman received one-third. This division recognized the contributions and value of both partners within the marriage.(36)

These cultural and artistic representations highlight the importance of equality, cooperation, and mutual support within ancient Egyptian society and continue to inspire artistic expressions and interpretations in different periods.

Marriage held great significance for both men and women in ancient Egypt. It symbolized their transition from being solely sons and daughters to becoming heads of their own households. Marriage provided social independence and the responsibility of managing the household fell upon the man and woman respectively. Additionally, procreation and childbirth were highly valued in ancient Egyptian society. A man without a woman to take care of him or a woman without a man would have been socially unacceptable.(37)

In Sinai, Bedouins preferred early marriage and celebrated the birth of children, particularly boys, with joy and delight.(38)

I recall an incident that occurred a few years ago when I was traveling in a microbus. I sat next to the driver, who seemed to be a leader among the other drivers. He was speaking on the phone anxiously, arranging for the marriage of a young, troubled driver who was causing problems within the community. When I asked why they didn’t just expel him, the driver explained that by getting him married, he would gain certain emotions he lacked, which would ultimately lead him to calm down and strive to become a better person. This philosophy reflects the belief of many Egyptians that marriage is a transformative and positive path in life. This can be seen in the metaphor used by grooms when proposing, as they often express their desire to “complete their faith” by asking for the hand of the potential bride.

- Changes over time, and the challenges or criticisms it faces in contemporary African society

Now, let’s discuss the changes that have occurred over time and the challenges and criticisms that marriage faces in contemporary African society. One common criticism is the excessive bride price, known as Shabka or Mo’akhar, demanded by some families for their daughters. Another issue is the interference of parents, particularly mothers, in the lives of their sons and daughters.

There are certain traditions that have been abandoned or neglected by people over time. One such example is the practice of blood mixing, known as Tashreet, among the Fadiga tribes in Nubia. Prior to the wedding day, the groom and bride would sit next to each other and cut their right legs, allowing their blood to fall into a plate and mix together.(39)

Another tradition that is no longer observed is “Dokhla Balady,” which involved the groom and bride entering their room on their wedding day while their families, relatives, and even friends and guests waited outside. The groom would then come out with a white handkerchief stained with blood, which was considered a test of the bride’s virginity. If she was found not to be a virgin, her family would be ashamed, and in some cases, she could even face harm or death. This tradition was more prevalent in rural areas and impoverished neighborhoods in cities.

These outdated customs have been criticized and are no longer widely practiced due to the changing values and awareness of women’s rights and autonomy in contemporary society.

There have been several changes and adaptations to traditional marriage customs in modern Egyptian weddings, influenced by Western-style celebrations. Here are some examples:

- D.J.s instead of bands: In contemporary Egyptian weddings, D.J.s have become the primary source of music instead of live bands. In the past, wedding parties would feature bands, singers, and belly dancers as the main entertainment. However, nowadays, most parties rely on D.J.-dominated programs, with bands being less common.

- Nubian ceremonies: Nubian wedding parties, whether held in cities or in Nubia itself, have undergone changes and adaptations. In Kalabsha, for instance, a variation in the Fattha process has emerged. The bride’s family rents a public venue called “Madyafa” to host the groom, his friends, and relatives. The groom announces his desire to marry their daughter during this event. While the groom buys a high-quality cake, the bride’s family covers the cost of renting the venue, which can be double the expenses of the wedding party itself.(40)

- Adopting traditional shows in Zaffa: Traditional wedding styles such as “Dameittan, Alexandrian, Baladi, Bedouin” are now incorporated as short shows within the Zaffa (wedding procession) or included in the wedding party’s program.

- Venues vs. streets: In the past, it was common for wedding parties to take place in the streets or open areas. However, nowadays, most weddings are held in venues such as hotels or clubs.

- European attire: The attire of the groom, bride, and many guests has become more Europeanized, especially in urban areas. Additionally, the bride now throws her flower bouquet backwards at the end of the party, and the first single, young female guest who catches it is believed to have a good omen as the next potential bride. In the past, it was customary for the bride’s single female friends and relatives to pinch her knee for good luck. Furthermore, the unified dress code of the bride’s maids is a modern European tradition.

References:

1- Ancient Egyptian Wedding Customs, available on: https://www.historyforkids.net/ancient-egyptian-wedding-customs.html#:~:text=In%20ancient%20Egypt%2C%20there%20wasn,families%20would%20also%20exchange%20gifts.

2- EGYPTIAN WEDDING GUIDE, available on: https://julianribinikweddings.com/egyptian-wedding/#:~:text=When%20the%20couple%20gets%20engaged,a%20marriage%20that%20never%20ends

3- Ibid.

4- Ibid.

5- COMPLETE LIST OF EGYPTIAN WEDDING TRADITIONS, available on: https://www.clarencehouse.com.au/wedding-tips/complete-list-of-egyptian-wedding-traditions/

6- EGYPTIAN WEDDING GUIDE, available on: https://julianribinikweddings.com/egyptian-wedding/#:~:text=When%20the%20couple%20gets%20engaged,a%20marriage%20that%20never%20ends

7- COMPLETE LIST OF EGYPTIAN WEDDING TRADITIONS, available on: https://www.clarencehouse.com.au/wedding-tips/complete-list-of-egyptian-wedding-traditions/

8- EGYPTIAN WEDDING GUIDE, available on: https://julianribinikweddings.com/egyptian-wedding/#:~:text=When%20the%20couple%20gets%20engaged,a%20marriage%20that%20never%20ends

9- Folklore Magazine, Issues 30-31: Jan.- June 1990, The General Egyptian Book Organization publications, “Bishari: the desert`s dwellers”, by Nadia Badawy, p.93-94

10- 10 FACTS ABOUT EGYPTIAN WEDDING TRADITIONS, available on: https://www.ask-aladdin.com/all-destinations/egypt/blog/facts-about-egyptian-wedding-traditions

11- Egyptian Wedding Traditions Worth Learning About, available on https://www.weddingdetails.com/egyptian-wedding-traditions-worth-learning-about/#:~:text=Traditional%20Egyptian%20wedding%20gifts%20include,are%20a%20symbol%20of%20fertility

12- EGYPTIAN WEDDING GUIDE, available on: https://julianribinikweddings.com/egyptian-wedding/#:~:text=When%20the%20couple%20gets%20engaged,a%20marriage%20that%20never%20ends

13- 10 FACTS ABOUT EGYPTIAN WEDDING TRADITIONS, available on: https://www.ask-aladdin.com/all-destinations/egypt/blog/facts-about-egyptian-wedding-traditions

14- Ancient Egypt: From Ptolemy II to Ptolemy IV, vol. 15, by Selim Hassan p. 98-99

15- Op. cit. p. 300-302

16- Op. cit. p. 363- 365

17- Folklore Magazine, issues 74-75, April- Sep. , issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Symbolism and marriage in Egyptian Nuba”, by El-Sayd Hamed, p. 26

18- Folklore Magazine, issue 100, Jan.- Dec. 2015, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Nuba`s Wedding Ceremonies”, by Safwat Kamal, p.63-64.

19- Folklore Magazine, Issue 5, Feb. 1968, Ministry of Culture, The General Egyptian Publishing Organization, “Sinai: its customs and traditions”, by Mohammad Tolba Rizq, p. 91-92.

20- Folklore Magazine, Issues 30-31: Jan.- June 1990, The General Egyptian Book Organization publications, “Bishari: the desert`s dwellers”, by Nadia Badawy, p.93-94

21- Folklore Magazine, issue 85, Jan.- Feb.- March 2010, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Egyptian Folk Wedding Celebrations”, p. 64-65

22- Folklore Magazine, Issues 30-31: Jan.- June 1990, The General Egyptian Book Organization publications, “Bishari: the desert`s dwellers”, by Nadia Badawy, p.93-94

23- Ancient Egyptian Wedding Customs, available on: https://www.historyforkids.net/ancient-egyptian-wedding-customs.html#:~:text=In%20ancient%20Egypt%2C%20there%20wasn,families%20would%20also%20exchange%20gifts.

24- Egyptian Wedding Traditions Worth Learning About, available on https://www.weddingdetails.com/egyptian-wedding-traditions-worth-learning-about/#:~:text=Traditional%20Egyptian%20wedding%20gifts%20include,are%20a%20symbol%20of%20fertility.

25- How Egyptian Weddings Stay Traditional With a Mix of Modern Updates, available on : https://www.theknot.com/content/egyptian-wedding-traditions

26- Egyptian Wedding Traditions: Everything You Need to Know

by Marisa Jenkins, available on: https://weddingfrontier.com/egyptian-wedding-traditions/

27- How Egyptian Weddings Stay Traditional With a Mix of Modern Updates, available on : https://www.theknot.com/content/egyptian-wedding-traditions

28- Egyptian Wedding Traditions: Everything You Need to Know

by Marisa Jenkins, available on: https://weddingfrontier.com/egyptian-wedding-traditions/

29- Folklore Magazine, issue 100, Jan.- Dec. 2015, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Nuba`s Wedding Ceremonies”, by Safwat Kamal, p. 74-75

30- Folklore Magazine, Issue 5, Feb. 1968, Ministry of Culture, The General Egyptian Publishing Organization, “Sinai: its customs and traditions”, by Mohammad Tolba Rizq, p. 91-92.

31- Folklore Magazine, issue 100, Jan.- Dec. 2015, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Nuba`s Wedding Ceremonies”, by Safwat Kamal, p. 51.

32- Folklore Magazine, Issues 30-31: Jan.- June 1990, The General Egyptian Book Organization publications, “Bishari: the desert`s dwellers”, by Nadia Badawy, p.93-94

33- Folklore Magazine, Issues 74-75 April-Sep., issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Tradition, The General Egyptian Book Organization,

“Ababda and Bishari in Halaib triangle, my experience in Shalateen”, by: Sonia Wali El-Din, p. 84.

34- Ancient Egypt: from Ptolemy II to Ptolemy IV, By: Seliem Hassan, Vol. 15, p. 645-667.

35- The State of Matrimony without the State: New Kingdom Egyptians and Marriage

By Grigorios I. Kontopoulos, available on : https://www.asor.org/anetoday/2016/11/new-kingdom-egyptians-and-marriage/#:~:text=But%20the%20purpose%20of%20marriage,important%20for%20the%20ancient%20Egyptians.

36- Ancient Egypt: from Ptolemy II to Ptolemy IV, By: Seliem Hassan, Vol. 15, p. 645-667.

37- The State of Matrimony without the State: New Kingdom Egyptians and Marriage

By Grigorios I. Kontopoulos, available on : https://www.asor.org/anetoday/2016/11/new-kingdom-egyptians-and-marriage/#:~:text=But%20the%20purpose%20of%20marriage,important%20for%20the%20ancient%20Egyptians

38- Folklore Magazine, Issue 5, Feb. 1968, Ministry of Culture, The General Egyptian Publishing Organization, “Sinai: its customs and traditions”, by Mohammad Tolba Rizq, p. 91-92.

39- Folklore Magazine, issue 100, Jan.- Dec. 2015, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Nuba`s Wedding Ceremonies”, by Safwat Kamal, p. 73-74.

40- Folklore Magazine, issue 85, Jan.- Feb.- March 2010, issued by Egyptian Society for Folklore Traditions, The General Egyptian Book Organization, “Egyptian Folk Wedding Celebrations”, p.64-65.